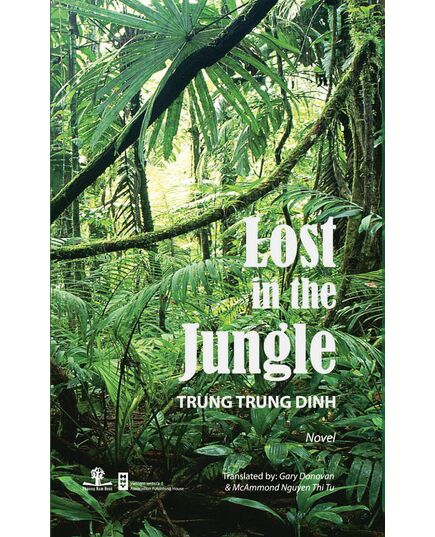

Lost in the Jungle (Sách tiếng Anh)

978604531542

Từ nhà sách đầu tiên năm 1982, Nhà Sách Phương Nam đã trở thành hệ thống nhà sách uy t...

Lost in the Jungle

Picture a northern Vietnamese teen-age soldier imprisoned in a jungle cave watching frogs and rats being roasted on an open fire and you are immediately drawn into what can only be described as a very special if not unique story. What makes this tale such a gripping and at the same time significant one? There are at least two subjects to consider for the purpose of grasping it s importance. The first is the process around which this novel was written and something of its illustrious history. The second is coming to know and appreciate the Vietnamese author Pham Trung Dinh (pen-name Trung Trung Dinh) himself.

“Lost in the Jungle” has won a prestigious State Prize in Vietnam, one of two which its author Trung Trung Dinh has been awarded over the years. For the western reader this may constitute an appealing, but, on the other hand dubious, distinction. We don’t really quite yet ‘get’ the post-war “Socialist Republic of Viet Nam”. What does a State Prize from a “Communist” government signify? At a minimum we know there is recognition that the story is well told and has cultural, historical or social value. The current government of Viet Nam is big on rewarding personal ethics and contributions to one’s community or the common good. So let’s leave the reasons for the choice of a State Prize by a government so different from our own – is it really? – and concentrate instead on what we in the West might learn from this jungle tale and how its English version came about.

Most of us are in the dark when it comes to appreciating the arduous and creative tasks that go into the telling and translating of a chronicle of this kind. This is not a longish novel. Perhaps that is a good thing when you think of the effort that must go into translating lively Vietnamese prose into English. These are two very diverse languages, the first based so fundamentally on tonal qualities and perhaps closer to Chinese or even ancient Hebrew for its earthiness and concreteness. English is every bit as creative and versatile but much more linear and certainly much more forgiving or limited when it comes to number of tones in speech or as demonstrated in writing.

The Vietnamese version of this book has been out for almost a decade and the decision to bring it to a Western (English-speaking) audience was only reached a few months ago. But translating fiction is not an easy task. Legal documents and verbal explanations, in a court room for example, call for accuracy. “Just tell me exactly what the person has said and don’t give me any interpretation of the words or your opinions.” I’ve often had to say that to my own translators as I worked and traveled in Viet Nam. Translating story is quite different. One must labour both with the words but also with the creative ideas and neither one of these must be sacrificed to the other. It takes Dr. Gary Donovan, a specialist in both linguistics and the pedagogy of linguistics to patiently struggle with the rough English translation to bring out both a faithful rendering of the author’s words plus a meaningful expression of ideas in a totally dissimilar language-type. This is a different level or constituency of creative expression. It also takes the quiet genius of cultural appreciation plus a full knowledge of the Vietnamese language of celebrated short story writer McAmmond Nguyen Thi Tu to provide a level of insight into meaning both of words and ideas, culturally shaped as they inevitably are.

Consider something as simple as the title of this book “Lost in the Jungle”. Around a dinner table in Calgary, Canada with the author, Dr. Gary, Tu and husband David; or in the Volga Hotel in downtown Ha Noi, again with author Dinh, plus a distinguished professor – friend – writer – and army comrade, and myself: we all weigh the pros and cons of changing the title to properly reach a Western audience. Some of us argue that “Lost in the Jungle” sounds too much to our Western ears like an old Tarzan movie. Back in Canada, those working day and night on an accurate yet appealing translation hold tightly to a faithful rendering of the original. And what does “lost” signify? I, myself, listened while Dinh and his faithful colleague and professor of literature Nguyen Van Loi reiterated the importance of allowing the reader the right of determining what might be meant by that word and that title. And in the end simplicity and verity won the day. Now, you gentle reader, are left to supply your own interpretation of events, which is as it should be in any great literature and is certainly in keeping with Trung Trung Dinh’s intent.

One final comment on the substance of this story and its process serves as a convenient bridge to some words about Pham Trung Dinh, the man. This is a story which centres on very young soldiers. Perhaps the real strength and contribution of this narrative is that it is told innocently, candidly, sometimes confusedly, through the eyes and ears, ideas and fears, feelings and tears, of a very young and sensitive man. That man is as in all good fiction a compilation of real figures not the least of which is Trung Trung Dinh himself. If we take nothing else from this story I hope it will be a deep appreciation of the author’s capacity for re-imagining those days in his own life and the perceptive nature which enables and enhances the recall. In addition there is the determination (nine years of work) to tell this – his? – story to others.

Loại sản phẩm

Bìa mềm

Kích thước

13x21x0.9 cm

Số trang

150

Tác giả

- Trung Trung Đỉnh

Nhà Xuất Bản

- NXB Hội Nhà Văn

Đơn Vị Liên Kết Xuất Bản

Phương Nam Book

Sản phẩm này chưa nhận được đánh giá nào. Bạn hãy là người đầu tiên đánh giá nhé!

Please sign in so that we can notify you about a reply